Business architecture is here and here to stay. We see it increasingly leveraged in strategic ways, with an emphasis on its role in enabling effective strategy execution, transformation, decision-making and more. However, we are now at a critical reflection point – even arguably a critical inflection point. While an incredible amount of formalization has occurred within the discipline and should be celebrated, the next frontier must focus more on getting (and sharing) practical results, socializing with a much broader group of people, and building architecture as a profession.

In this StraightTalk installment, we firmly establish the idea of business architecture as a real discipline with a reliable career path. We first explore the topic through an academic perspective and then through the broader lens of architecture as a profession that includes all architectural disciplines in business and technology. To do this, we have brought in two worldwide authorities to share their perspectives and visions on the topic, Dr. Brian Cameron and Paul Preiss.

About our guests

Dr. Brian Cameron is the Associate Dean for Professional Graduate Programs in the Smeal College of Business at the Pennsylvania State University. He is the Founding Director of the Center for Enterprise Architecture at Penn State. He developed the first online enterprise architecture master's program in the world and is the Founding President of the Federation of Enterprise Architecture Professional Organizations (FEAPO). The first part of this installment is based on our podcast with Dr. Cameron, Business Architecture in Academia, where he gives us a pulse on business architecture in academics today and shares his vision for the future.

Paul Preiss is the Founder and CEO of lasa Global, the largest worldwide non-profit association for all architects. In addition to his serious architecture leadership and chops serving in Chief Architect roles, he has been the leading voice worldwide for architecture as a profession. The second part of this installment is based on our podcast with Paul, Architecture as a Profession, where he talks about what it really means for architecture to be a profession, where we are today, and what is possible for the future.

Disclaimer: we’ve abbreviated the responses a good bit and made some adjustments for our typical StraightTalk-style: the headings represent StraightTalk asking the questions and our guests, Brian and Paul, respond in turn. Make sure to check out both podcasts firsthand as they contain all of the rich conversation and insights not fully included here. Seriously, both of these podcasts are must-listens.

Dr. Brian Cameron: Business Architecture in Academia

“I think the promise for business architecture in academia is that of a facilitator of strategy execution and a discipline that informs business strategy.”

“If you look at many stats from Michael Porter and others, the failure to execute strategy is one of the largest challenges in all organizations today. Yet we really don't address it in business programs. So I think there's a need and I think business architecture fills that need. We just have to bring together the need with the solution across academia.”

“I personally believe that if business architecture is going to become a discipline – an established discipline in the same way we view accounting, law, medicine and other established disciplines – you have to have some type of academic programs in order to achieve that level of recognition, understanding, and professionalism.”

What is the state of business architecture in academics today? Is business architecture recognized as a discipline? Are the concepts embedded in other courses or degrees?

Brian: “I think it's fair to say that business architecture is very much in its infancy in academia, at least in large research universities like Penn State. It's largely an unknown topic in academia. If a faculty member has heard of business architecture, it's often in what I'll call a more dated IT context. As we all know, business architecture in most organizations grew up in IT under enterprise architecture. But I think that discipline has evolved greatly from those days. In many organizations, business architecture is now part of a business function like strategic planning, but it's largely unknown, unrecognized in academia.

However, we are starting to change that slowly. I think the promise for business architecture in academia is that of a facilitator of strategy execution and a discipline that informs business strategy. We're just starting to make those inroads. I have a strategy execution course that I teach at Penn State with business architecture as a facilitator of strategy execution. It's gaining a lot of traction with a wide variety of audiences in our different masters programs.

We're looking at how we take that success and get the word out across academia. As part of that, we're starting to sponsor joint research projects with some industry associations and some academic associations around strategy execution and how strategy execution is taught at different universities. I think there's a lot of opportunity for business architecture, but we're very much in our infancy in academia at this point in time.”

What type of people are in your Graduate Certificate in Business Architecture program at Penn State? What concepts do you find to be resonating?

Brian: “Our graduate certificate in business architecture is three courses and nine credits. It is unique and I haven't seen anything like it anywhere else in the country [USA]. As I mentioned earlier, it focuses on business architecture as a facilitator strategy execution. In contrast to the training providers, which are typically in my experience more down in the weeds focused on modeling, we talk about modeling, obviously, but it's more from a strategic standpoint along with how to position business architecture as a facilitator of strategy execution.

The unique thing about the Penn State online portfolio is that the course will be offered as a required part of some programs and as electives in others. So, I literally have seven or eight different master's program audiences coming together. For example, I have students from our enterprise architecture masters program where this course is required, and I also have students from our online MBA where it is an elective. I have students at a very senior level from our online masters in strategic management and executive leadership – people with 10 plus years of experience that actually do the strategic planning. And, I have people from our online masters in corporate innovation and entrepreneurship. I have all these different audiences coming together in the course and it's working out really well. They all bring different perspectives and different viewpoints, and it really makes for a rich team experience and a rich learning environment.”

What type of education do you think is necessary for business architecture practitioners to succeed in the role? Is some type of formal education through a university required?

Brian: “I personally believe that if business architecture is going to become a discipline – an established discipline in the same way we view accounting, law, medicine and other established disciplines – you have to have some type of academic programs in order to achieve that level of recognition, understanding, and professionalism. I think we have a way to go before we're quite at the level of established, recognized disciplines like accounting that everybody understands.

There are also challenges. We talk about what type of education should be in such a curriculum. I'd say that today organizations are roughly split. Less than 50 percent of the business architecture groups today sit under traditional enterprise architecture, which traditionally sits under IT, but that number is becoming less and less every year. Those groups are more IT-focused and are often populated by people that come from IT, which are oftentimes more IT process and capability-focused modelers. This used to be the majority, but there’s been a transformation going on over the last several years. Then, there are business architecture groups that are part of business functions such as strategic planning. They come from more of the business background, and are modeling at more of an organization-wide scope and often work more at a strategic level. They are typically viewed as a strategic resource for the entire enterprise.

I'm going to argue that we should be building out our education programs for the latter group, the people that are enterprise-wide and more of a strategic function. I would say that's the more forward-looking direction versus the IT-focused groups. I would argue that there's education that both groups need, but it shouldn't be overly IT-focused as some programs, certificates, and training programs might be today. The big challenge is helping people bridge into more of a strategic business function, which means they need to understand things like strategic planning, organizational development, and organizational design.”

What type of technology foundation do people need to succeed?

Brian: “I've had people tell me that those in this role should be able to understand business as well as or better than they understand technology. For the business architecture groups that sit under IT, I would argue that’s probably not the case today. On the other hand, it's not enough to have people coming out of an MBA program who just understand the business side. They need a good foundation of enterprise technology in order to get the execution piece down. If you can't go that deep, you're not going to be quite as effective.

So, we really need kind of a Renaissance person that understands enterprise technology and business equally well and can wear different hats at different times and be the bridge that's missing in many organizations between strategy and execution sitting on the business side. Execution usually involves technology today. Technology is pervasive in everything you do and you need those bridge people that understand both.”

What are some common career paths that you see people take, both as they move into the business architect role and when they are ready to take their career to the next level?

Brian: “There is no standard career path for business architecture professionals – or enterprise architecture professionals for that matter. People come into these professions through many different twists and turns in their careers and from many different backgrounds. You might have somebody that starts more on the business side and might have a business degree and then through some twist or turn, gets exposed to business architecture and falls in love with it. I've had people in my class that feel they found their calling in life – that the strategy execution middle ground is where they are meant to be. You also have people that start as a business analyst or in an IT role and then get exposed to the business architecture and feel they found their calling so they might be moving up through a technical path. You have people that started maybe in an innovation group and then get exposed to business architecture and see it as a mechanism to connect dots across the organization that no other group has access to or can see. And there are many others. I don't know that there are one or two standard paths. I've run into people with liberal arts backgrounds or psychology backgrounds and all different types of backgrounds that through different twists and turns, found themselves in business architecture.

I do think that we need more formalized progression paths in organizations though. This is a problem I see in many organizations where business architecture does not have a well-developed career path. If someone wants to go into business architecture, where can they go and what is the progression path? I think a career path is another key component of having an established discipline.”

Thinking about our business and technology leaders of tomorrow, do you see business architecture as part of MBAs and other degrees in the future? What is your vision?

Brian: “That's one of the challenges with academia. If business architecture is going to be accepted, it's got to plug into an established area and it can't be all things to all people. So, we have to kind of decide: what do we want to be when we grow up?

I would argue that MBA programs should have a concentration in strategy execution. I think we’re going to get better acceptance if we start with strategy execution and then say, oh, by the way, this discipline is generally known as business architecture. I think that's likely a better approach to get in the door so others can see what we can bring to the table.

So, yes, business architecture can be a concentration in MBA programs, but we’re also seeing more higher level strategic management and executive leadership masters programs come onto the scene. I would argue in those programs that a concentration in business architecture can be very useful as well.

I think that those two types of programs are really the future and the promise for business architecture in academia.”

What are your perspectives on lifelong learning?

Brian: “We have a whole portfolio at Penn State in the College of Business focused on lifelong learning, from noncredit education to short courses to graduate certificates to masters degrees that stack all the way through into the future. We're even looking at a possible executive doctorate in business administration. So you go through every continuum of the career field. And I think that's what's needed today.

However, in many organizations today, it’s not enough just to have one type of degree. So, we are seeing the masters degree become very much as the bachelor's degree was, say 30 or 40 years ago. People are getting their masters degrees younger and younger, and they get them at a very early age. And then they see that, lo and behold, everybody's got a master's degree. What do I do next? Do I get a second master's degree? This is where the executive doctorate in business administration is becoming more popular as perhaps the next step for some people.

I think it's important to have a curriculum that allows people to what we call stack degrees. We give people a path to earn multiple masters degrees in a faster and cheaper fashion than they would if they were getting each degree separately. I think that's really part of the whole lifelong learning – being able to mix and match things together and build upon what you've already done to generate some economies. It gives you a quicker, cheaper path to that next step in your educational journey. I think we're ahead of most in this area, but this is definitely a trend for higher education in the future.”

Do you have any final words you would like to leave us with?

Brian: “I'm encouraged with the response I've received from a wide variety of audiences for business architecture and its role as a facilitator of strategy execution. I saw this as a problem area in our curriculum and in business. If you look at many stats from Michael Porter and others, the failure to execute strategy is one of the largest challenges in all organizations today. Yet we really don't address it in business programs. We give it some lip service, but we really don't talk about or have any focused courses on strategy execution. So I think there's a need and I think business architecture fills that need. We just have to bring together the need with the solution across academia. Over time, I think we will put the pieces together and spread knowledge on what business architecture can bring to a business. Curriculum change will be slow. Academia does not change quickly, but I think over time you'll see these types of courses proliferate at other universities.”

Paul Preiss: Architecture as a Profession

“A profession is really a commitment to rigor in the development of our skill sets and creating stabilized outcomes at critical points in our career, for society and for our employers and clients.”

“We've got to accept that architecture can have one fundamental purpose to society – simple enough for anyone to understand. As architects we’ve got to be clear on the value we offer to society, and it has to include both business and technical outcomes. It can't be one without the other.”

“Do you realize that hairdressers are more professionalized than we are as architects? Your hairdresser has to have a license and rigorous training, but we can build a sociotechnical system that controls peoples’ lives in software.”

What does it mean for architecture to be a profession? What is required for designation as a profession?

Paul: “Profession is such an overused term in our field. People talk about being professional. People talk about having a profession, but nobody stops to think about what that really means. It means adhering to a constant set of concepts that guide the things that we depend on as a society.

We're just kind of starting to see a glimmer of hope coming out of a pandemic. The hope came from doctors, nurses, people who are real professionals. Now, what does that mean? I am an utter and complete supporter of business architecture, just like I'm a supporter of software architecture and infrastructure architecture and information architecture, etc. But the active term in there is architect. In most organizations, you just get to call yourself an architect. I have somebody in my class today who was just handed the title, so now they are taking the class so that they know what architecture is. When you think about it, that's a really weird world. It would sort of be like showing up at a hospital and going, you know, I want to be a doctor so I'm going to start cutting into people and then I'm going to take a class on being a doctor.

Real profession is about a career path. It's about the infrastructure that underlies creating architects with a rigorous competency model and specific experiences that are recognized – but more importantly that are recorded. For example, a real profession requires that we see and document that we saw this person successfully facilitate meetings on developing an innovative business model, work with technology strategy, etc. That's how doctors are created. That's how accountants are created, and lawyers and, building architects.

Do you realize that people oftentimes don't pay for their own architecture training? They expect their company to do it. Imagine if doctors didn't pay for their own education. We'd have no doctors.

Do you realize that hairdressers are more professionalized than we are as architects? Your hairdresser has to have a license and rigorous training, but we can build a sociotechnical system that controls peoples’ lives in software.

For example, our bank systems are created by the person or group that bid the lowest on the RFP. Our privacy, our health care, etc., is all created by people who literally have random backgrounds if we consider the sheer variety of people who call themselves architects today. It's absolutely wonderful from a personal perspective, but not from a professional designation or a professional delivery of excellence. It’s like rolling the dice when you when you hire somebody. Even the largest consulting firms in the world train all their own architects in random ways on random stuff. I've got visibility into these training groups and these architect academies and they're all different. It’s like each of them creating their own internal medical schools from scratch, based on random people and what they think of architecture.

So, profession is really a commitment to rigor in the development of our skill sets and creating stabilized outcomes at critical points in our career, for society and for our employers and clients.”

Where do you think we’re at today in terms of architecture as a profession?

Paul: “Since I started this 20 years ago, I have believed in the same message since day one because I read the history of the AIA (American Institute of Architects). The AIA history says that 13 people got together in 1857 with the goal of forming an organization to promote architects and architecture. But the number one reason for the AIA was that buildings were falling over because anyone could call themselves an architect. So, I've been a believer in profession over a particular body of knowledge. I don't care if you use a strategy scorecard or a business model canvas or if you have a capability model. I care that you know when to use those things and have done so rigorously.

At Iasa, we can stably create a business architect, a software architect, a solution architect, etc. and they'll all still have the same background, even if their day in and day out work is different. They'll speak the same language. They'll have the same competency model and they can grow their career stably.

So where are we now? The world is waking up and realizing that with all these people working in technology, especially considering that technology's impact on society is now becoming so monstrous, we need to act. We’re starting to see regulation. We're starting to see governments get involved in this. We're starting to see competency models across the EU as well as globally. Privacy is a major concern and that or regulation will speed us along. There are also some ideas related to ethics, but honestly, we are still far away from the kind of professional infrastructure we need. We're still, I'd call it 30 percent there compared to where we need to be as a profession.”

What could architecture look like as a profession in our most ideal state?

Paul: “Not everything is going to be a profession. There’s this wonderful Harvard professor [Richard Barker, see More Good Stuff] who wrote why management is not a profession because anybody needs to be able to start and run a business. However, professions have a societal benefit. And this is why I don't understand why we don't do it for architecture. We can half the cost of hiring architects and half the cost and time of developing systems – and I mean business systems, I'm talking about systems of people, process, and technology. So, we could live in a world that is going to be faster, better, and cheaper to a degree, but we're also not going to have as many failures. Not nearly as much technical debt or silly, useless systems that don't deliver business value. There's a really massive need for privacy and for efficacy in decision-making, where organizations need a cross-enterprise view of how business and technology work together.

This is all within reach with within a 10 year span. If we will professionalize now, 10 years may sound like a long time, but for comparison, it's been 20 years since the Agile Manifesto was signed and we're still figuring out how to make it work. I'd like to just start thinking about safer systems, more sustainable systems, more value-oriented systems and doing so at costs, simply speaking, orders of magnitude cheaper than they are today.

We are just sort of cave people compared to the kind of sophistication we would have if we would just take on something as straightforward as a profession. Think about all those consulting architects I was talking about and if they were all educated in our academy right after they got out of school. That is billions of dollars of training saved, billions of dollars of mistakes avoided, and billions of dollars of value created for those consulting companies that then give them jobs.”

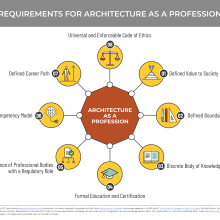

Check out the handy summary below on what’s required for architecture as a profession.

What are some of our key challenges to achieving that vision?

Paul: “Did you ever want your parents to come back from their vacation early when you were a teenager? Not really, that’s the whole point. We like the cowboy mentality. Technologists still have this sort of garage shop mentality and ideas around what it means to be a real architect or a real technologist. That's one of our big obstacles. We’ve got to start to venerate not just the hottest programmer in the room but venerate people who actually create value.

Furthermore, we've got to accept that architecture can have one fundamental purpose to society. This one is stopping us really bad when the end. You never go to a doctor to get your taxes done. I care about the one value proposition that my grandma can understand. She doesn't have time to understand all of the nuances and neither does your CEO or any of your stakeholders. We get to say, we as architects offer this value to you, society, and that has to include both business and technical outcomes. It can't be one without the other.

We are our own worst enemies because we love to argue and we love to get in each other's faces and say, you're not a real architect.”

What would it take to really unite all of us as architects? And where should we start?

Paul: “What it really takes is for us to stop thinking that each of us is a unique snowflake and to band together and represent each other effectively. We've got to stop working against each other. That means we need to create a common career path. The day in and day out jobs of a business architect, solution architect and let's say infrastructure architect should be very different – their environment, stakeholders, deliverables, etc. – because they are fundamentally creating different things. But the problem right now is they're also fundamentally different professionals that don't speak the same language. It takes working together under an umbrella and creating a common career path where our newest architects are going through a common process and then they specialize.

I believe that the number one success factor of an architecture practice is how well they practice together. How they solve their engagement model problems together, and that regardless of reporting structure, they are based on the same competency model. That really is the killer app. Whoever gets the competency model right that gets adopted, that will give us our baseline language. Then you can specialize to your heart's content. Doctors do it all the time.

With a common competency model and engagement model, having each other's backs, and staying focused on practical value, you will see a lightning round of growth in the value your stakeholders perceive as well as what you actually deliver.

Do you have any final words you would like to leave us with?

Paul: “I think during the pandemic, one of the things that we can say was a blessing is that people started to realize that these architectural decisions are important and we've seen a real rise in outcomes. So I would say, as a final thought, get focused on the rigor in your practice. I don't care what frameworks you use, use the BIZBOK® Guide, use SAFe, use SFIA plus all that stuff. But get rigorous about the concepts and the practical value of those concepts. Work out an engagement model with your architecture specialists that is inclusive of all of them and at all levels.

This isn't about the Chief Architect deciding everything for you. Did you know that the council that runs medical schools in the US actually has students on the council that vote for medical school policy? They do that because it's an inclusive process. They realize that student voices are the most important voices because they are future doctors. Create a living practice, a real practice of architecture in the same way that you would expect the rigor of a practice at a hospital to be.”

In Closing...

Now it's time for us to really ask ourselves What If…

- What if business architecture were widely recognized as a valid and highly demanded discipline and career path?

- What if academic programs were widely available to support the discipline and career path?

- What if MBA programs and other masters programs such as those focused on strategic management and executive leadership offered a concentration in strategy execution and business architecture?

- What if architecture was a true profession with all of the components in place?

- What if we could unify all architects and we were all part of one profession but with different specialties?

How much more successful could we be together as a force for change and good?

However, we also need to follow that What If with action and commitment. The road ahead to a unified architecture profession is completely doable. And the best part? We could provide entirely unique and important value to society – and professionalizing would only make us better and increase our recognition and success. But, we have to want that vision and be willing to do what it takes to achieve it.

More Good Stuff...

Business Architecture in Academia (StraightTalk podcast): Just in case you missed the link right there in the beginning, here’s the podcast with Dr. Brian Cameron where he gives us a pulse on business architecture in academics today and shares his vision for the future.

Architecture as a Profession (StraightTalk podcast): Just in case you missed this link right there in the beginning too, here’s the podcast with Paul Preiss where he talks about what it really means for architecture to be a profession, where we are today, and what is possible for the future.

Related StraightTalks: Here are a few select installments of StraightTalk that provide some helpful background: Post No. 72 on The Secret of business architecture; Posts No. 3 and No. 50 on business architecture and strategy execution; Posts No. 55 and No. 86 on business and technology decision-making; and Post No. 97 on business architecture strengths and team building.

The Big Idea: No, Management Is Not a Profession (Richard Barker, Harvard Business Review): An incredibly important and relevant article to inform our thinking about architecture as a profession and what that really means.

The Elusive Link Between Technology and Strategy (Brian Cameron, Biz Ed): An article published by Dr. Cameron within the distinguished academic publication, Biz Ed, which emphasizes the importance of effective strategy execution and strategic alignment – as well as the critical role that business architecture plays as an enabler.

Graduate Certificate in Business Architecture (Penn State): The program mentioned in Dr. Cameron’s podcast. Make sure to check it out.

Federation of Enterprise Architecture Professional Organizations (FEAPO) website: FEAPO is the worldwide association of professional organizations which have come together to provide a forum to standardize, professionalize, and otherwise advance the discipline of enterprise architecture.

Iasa Global website: Paul is the Founder and CEO of Iasa Global, the largest worldwide non-profit association for all architects. The site is a goldmine of resources and make sure to check out the ITABoK as well.

The Business, Innovation, Leadership and Technology (BIL-T) Conference Series: Check out the BIL-T conference series, sponsored by Iasa, which is a place for global conversations and debate on big picture perspectives and how to make a better future for our organizations. The events are free, the speakers are amazing, and the topics are highly relevant to architects.

The World of Architecture Needs Regulation and Professionalism (Paul Preiss, Architecture & Governance): An excellent article by Paul on the topic.

The Future Role of IT Architects? (Paul Preiss and Brice Ominski): A fantastic conversation with two leading architecture experts, taken from the Radical Innovation: The Future of IT Architecture BIL-T event.

Amateurs Versus Professionals (Farnam Street): While not referring to professions with the same concreteness as we have been discussing in this installment, there is good wisdom here to help us reflect on the seriousness and commitment with which we pursue what we do.

The Ultimate Deliberate Practice Guide: How to Be the Best (Farnam Street): Everything you need to know to improve your performance at anything, for beginners and experts.

What Reality Are You Creating For Yourself? (TED Talk): An enlightening TED Talk by Isaac Lidsky who lost his eyesight but learned to see. “Reality isn’t something you perceive; it’s something you create in your mind.” That means you have the power to change it.